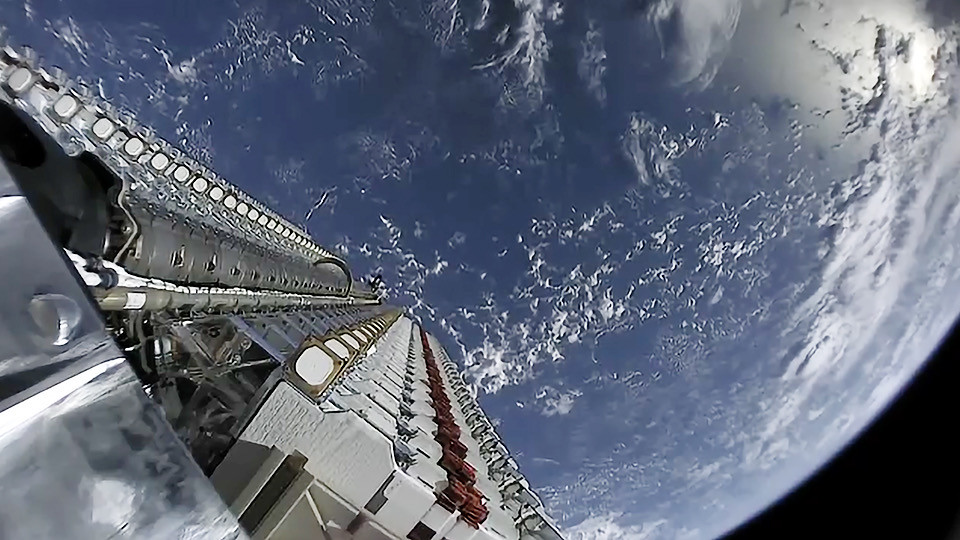

SpaceX is planning to launch the second installment of its Starlink megaconstellation on Monday (Nov. 11), and astronomers are waiting to see — well, precisely what they will see.

When the company launched its first set of Starlink internet satellites in May, those with their eyes attuned to the night sky immediately realized that the objects were incredibly bright. Professional astronomers worried the satellites would interfere with scientific observations and amateur appreciation of the stars.

“That first few nights, it was like, ‘Holy not-publishable-word,'” Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told Space.com. “That kind of was the wake-up call.

SpaceX and its leader, Elon Musk, reassured astronomers that once the satellites settled into place, they would stop masquerading as the stars they are named for. McDowell wanted to confirm the accuracy of Musk’s statement, so he asked an email Listserv of amateur astronomers to wait for the first batch of Starlink satellites to reach their final orbit, then compare the brightness of specific satellites to the stars around them.

Those observations started in July. McDowell hasn’t completed an exhaustive analysis, but he said the preliminary results are concerning, with Starlink satellites regularly clocking in at magnitudes between 4 and 7, which is bright enough to see without a telescope. “The bottom-line answer is, you can consistently see these things,” he said.

The initial Starlink launch carried 60 satellites, but that’s just a tiny fraction of what SpaceX has described as its long-term plan, of launching tens of thousands of the devices in orbit. “When you’re talking about 30,000 satellites, and many above the horizon at any one time, that’s what’s new about this,” McDowell said. “It’s not going to be just the occasional interference, it’s going to be continual.”

McDowell and his colleagues specializing in optical astronomy aren’t used to having to ignore technology masquerading as astronomy. But it’s a position radio astronomers are quite familiar with, since satellites send data back to their humans in radio frequencies. “That was something that people realized was coming,” he said, “whereas the light-pollution aspect caught us by surprise.”

In response to the outcry, Musk said in May that he “sent a note to Starlink team last week specifically regarding albedo reduction,” which refers to the amount of light reflected by the satellites. In a separate tweet regarding the issue, Musk also said that SpaceX doesn’t intend to interfere with optical astronomy. “That said, we’ll make sure Starlink has no material effect on discoveries in astronomy. We care a great deal about science,” he wrote.

But McDowell complained that SpaceX hasn’t provided any details about what modifications the satellites could endure and how much they would dim. He hopes to repeat his brightness check once the Starlink satellites that SpaceX plans to launch next week reach their final orbits.

“We can hope that that will improve things, but let’s see, the proof is in the pudding, right?” he said. “All we can do right now is go on what they’ve actually put up there. And what they’ve actually put up there are really bright satellites that if you had many thousands of them would represent a serious change to the night sky.”

For McDowell, the concern is about more than Starlink or SpaceX specifically. “This whole new scale of space industrialization means that this is a problem that we have to start worrying about, and in fact, should have started worrying about 10 years ago,” he said. “I’m not trying to say we absolutely shouldn’t do megaconstellations. But let’s phase it in, let’s assess the degree of light pollution, let’s manage it as a resource.”

He hopes that the space community adopts general practices about how much light pollution individual projects can produce, paralleling existing guidelines for managing space debris. “We thought we could ignore the space age in astronomy, but it’s here,” McDowell said. “Now we have to take it seriously and deal with the impacts on ground-based astronomy.”

Posted on November 11, 2019 in Space News, Space Travel